Invisible House

Interview by Rosa Bertoli

Chris and Roberta Hanley take us behind the scenes at the Invisible House, the distinctive Joshua Tree monolith they created with architect Tomas Osinski. Known for their work in Hollywood (as producers of cult movies that include American Psycho and the Virgin Suicides), their cultural roots extend deep into the history of contemporary music and film. Passionate about architecture, together they have created a series of houses across the world. Cantilevered over the desert’s rocks, Joshua Tree’s Invisible House has a unique character that has made it a pop culture favourite over the years. We quiz Chris and Roberta about life and light in the house, and experiencing the desert through the architecture.

How did you end up in Joshua Tree?

Chris Hanley: We were living in New York, working in the music business and doing music videos, we started karaoke [in America], and worked with Andy Warhol and played music with Jean Michel Basquiat. Then Roberta decided we should go into film, so we ended up in California, where we made American Psycho and Spring Breakers and Virgin Suicides, and a whole lot of other movies.

We bought the land in Joshua Tree in 2006 and then played around being off the grid with prefabricated housing. To be able to live on the land, they told us we better design something bigger that would qualify for the building code of the area. So we just decided to go for it.

Can you tell us about the process of creating the house, what inspired you?

CH: When we started drawing this house, I was influenced by New York City skyscrapers, as that's where we spent a good part of our life. I was inspired by monoliths like Mies van der Rohe’s Seagram Building on Avenue of the Americans, and 2001 Space Odyssey. I drew it in pretty good detail and then went to an architect we had been working with, Tomas Osinski. The whole thing is really simple: a cantilever monolith 225 feet, 8 inches long, 21 feet high with refractive and reflective solarcool blue vitro glazing covering its exterior surface. About 100 feet on the west, south and north side slide open alongside the pool, so you can feel like it's indoors and outdoors. Literally sometimes animals come in.

Andy Warhol used to tell us that untouched pure land is the best art there is, and the land here has really nice shapes. So that reflective and monolithic object was supposed to be juxtaposed with the landscape, but then also blended in. We don't see it as a house per se: it's more like a sculpture, an artwork that you could live and create in.

It's interesting that the inspirations were very urban and connected to New York, yet the house is very much in contact with nature. It feels like there's a real conversation between the house and its surroundings.

CH: We are used to these big rectangles fitting into urban landscapes and going up really high. I think the rectangle is a universal form, it's always been in my head, but my idea was to flip it horizontally and cantilever it. So it's a juxtaposition.

Roberta Hanley: This is a house for incredibly civilised people who want to see nature without really having to engage directly, thinkers and visual people who like to look, and yet be protected from the elements. It reminds me of the [dioramas at the] Natural History Museum in New York. But then you venture out, and you are in the National Park. I go horseback riding for four or five hours, and I think it's very special.

How does the house change throughout the day?

CH: First thing in the morning, it's black, and then this orange corner comes up, and by noon it's almost invisible. And then at the end of the day, it picks up the sunset in the distance, reflecting the National Park mountains four or five miles away. It never looks the same, all day long. And then at night, there’s very little artificial light, so the stars and the moon give the light.

What was your approach to the house’s interiors?

RH: We decided not to have too much furniture, we wanted the interior to fit in with the grey concrete floors.

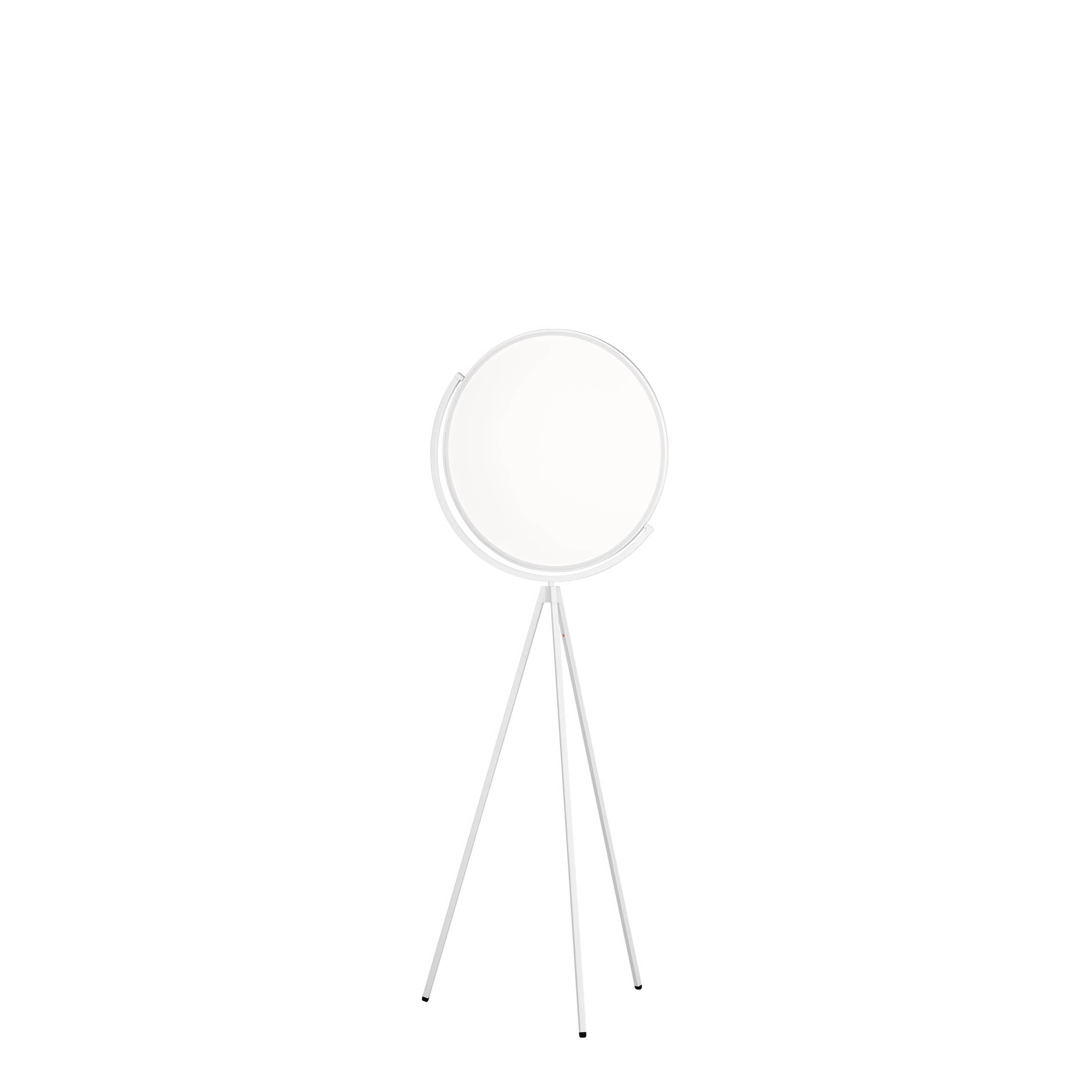

Flos came in and added a tremendous element of light. Chris had two 250 and 150 foot long lights, but I felt it needed a lot more than that, so that I can read a book and write a script. So it became really important to add some lights, and Flos has that minimalism that doesn't detract but yet, it allows you still to enjoy the space.

So now we have some lights outside near the firepit that are really minimal and monolithic. Before, we cooked practically in the dark, and suddenly, we had light, which was pretty cool. And playful as well: like above the bathtub, there's this symphony of lights that are just as if you're in a New York Theatre on Broadway.

CH: Looks like a constellation. It's like getting close to stars.

Otherwise, the house is very minimally furnished

RH: There's not a lot of knickknacks and silly things to annoy people and bring back memories. It's all about the new and the future, the house is about what you can do next, not what you are doing now. And I think that is the gift that we give to ourselves and to others who come in. People often say that while they were there, they had an amazing dream or brainstorm or a thought came to them like a lighting rod.

Can you tell us about your experience of the house?

RH: There aren’t many neighbours, and everybody seems like minded where they worship the desert and the rocks. We were very lucky, it's a perfect piece of land: it has just the right amount of flatness that you can take little strolls. There are really good paths that are just naturally there from forever. And it's really good for your brain. If you're a dreamer, you take the same walk every day, and you're able to experience lucid dreaming really easily.

The environment matters to us, I've always been an environmentalist. And I think that a house must have something that makes it livable and also creative. We're striving towards being really modern, meaning the house gives you something back, it keeps you alive, it makes you healthy and gives you an environment that also helps your sanity and your brain functions.

And Joshua Tree is perfect for that: the area is completely non polluted. It's two and a half hours from Los Angeles and the skies are absolutely blue, the clouds are puffy white bits of cotton. And the land is pure. It's just extraordinary.

Joshua Tree is very attractive to creatives; architects, artists. What’s been your experience of the culture in Joshua Tree?

RH: It's become quite the community. Because of us a few friends bought houses and it started to populate.

CH: In the 90s we all used to go to Joshua Tree and a lot of music was taking place. Billy Gibbons, ZZ Top and PJ Harvey recorded albums right in Joshua Tree. And so became a cluster of musicians and designers, architects.

RH: You could be creative and have your art studio there. It was the beginning of this incredible independent spirit.

Now Invisible House has made it on the news as you’re selling it…

CH: We were going to live in it, but then so many of our friends, actors and filmmakers, directors, producers came to the house and used it for long periods of time. Alicia Keys took it for a while to record music in it and then everybody was using it. And I thought, well, I guess we better just let people use it, they seem to be having a lot of fun. It's like when we make a movie; at a certain point you let it go in the world. And this house is already let go. This house has become this influencer thing.

RH: Chris's design ended up being so well loved, and it hasn't stopped. And what matters is that it stays as a historically important architectural specimen, and maintains its integrity.